Why consider a career in construction?

Construction is the largest industry in the country. Every American lives in the “built” environment – the product of the construction industry. This includes residential, commercial, and industrial buildings.

- The construction industry employs more than 7.7 million people in the US

- There will be millions of new jobs in the construction industry in the years ahead.

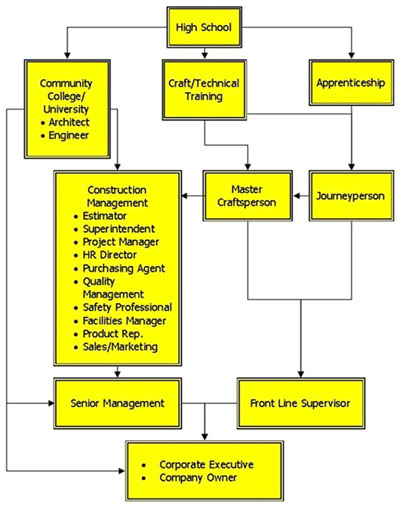

There are a lot of options and opportunities. The industry is as diverse as the structures it builds. Careers range from craft-level professions, Technical, Management, to Architects and Engineers, Office, Accounting and other support positions are also available.

- Diverse education levels are needed – Apprenticeships, Vocational training, 2-year or 4-year degrees.

- A variety of skills are used depending on the position: physical and manual dexterity, mathematics skills, problem solving skills, computer skills, and more.

- The average age of workers in the skilled trades nationwide is 48

- Baby boomers (born 1945-1950) have begun to retire and those positions, along with new ones, need to be filled.

What will your Career in Construction path look like?

Careers in Construction

a. Nature of Work

Managers must have up–to–date financial information to make important decisions. Accountants and auditors prepare, analyze, and verify financial reports, and then furnish this and similar information to the chief financial officer and other managers in the organization. They also verify the accuracy of their firm’s financial records and check for waste. Accountants/auditors typically work in the home office of a construction firm, and rarely visit the field office(s).

The chief accountant position assists the chief financial officer in handling the day–to–day operations of the accounting department. He/she is responsible for the detail work and supervision of the accounting personnel. He/she is usually responsible for compiling the information required for cash planning, monthly financial reports including budget and operating comparisons, general ledger accounts, and the financial statements.

b. Education and Training

Most construction firms require applicants for accountant and internal auditor positions to have at least a bachelor’s degree in accounting or a closely related field such as business administration. Applicants should be familiar with computers and accounting software.

c. Advancement Potential

With additional training, education, and experience, accountants and auditors may be promoted to top management positions, such as chief financial officer.

a. Nature of Work

A good secretary or administrative assistant allows the executive decision–makers to be efficient by providing those supporting services that will save time and provide organization of the work. Much of the work of an administrative assistant or executive secretary is routine, but often highly important. Listed below are some of the secretarial tasks of those presently working in the construction industry.

i. Sorts mail and often responds to letters that are of a routine nature.

ii. Maintains a schedule of appointments for those for whom she or he is directly responsible.

iii. Takes dictation and transcribes it.

iv. Does preliminary interviews of job applicants.

v. Maintains office efficiency by ordering supplies and being prepared for rush jobs.

vi. Types financial reports.

vii. Sets–up meetings.

viii. Often will organize social affairs for the company.

ix. May be responsible for the care of personnel records, including the coordination of vacation time.

x. Types various kinds of contracts and proposals.

xi. Meets and welcomes guests of the company.

xii. Handles correspondence.

b. Education and Training

A high school diploma appears to be an absolute necessity. In addition, a strong background in the basic secretarial skills is mandatory. This includes shorthand, transcription, typing, understanding business machines, and a strong working knowledge of English grammar and spelling.

Background training in business administration as the result of attendance at a junior college or school of business would also be helpful. Beyond these basic skills, however, is another important feature, namely attitude and grooming.

It is often true that the secretary will establish the basic tone of the office. In this regard a secretary must consider his or her attitude and grooming as an integral part of their career pattern. They must develop those personal skills and habits that have a positive effect on a variety of different people.

People under pressure need support, and the secretary/administrative assistant is often the best person to provide that necessary lift to make a working day more pleasant and profitable. Human relations skills, then, are no less important than the more mechanical skills of an efficient secretary.

c. Advancement Potential

Job conditions are generally good, though on occasion hectic. The rewards, however, are quite good with salaries at or well above those paid by other industries. In addition, the potential for advancement is excellent for efficient and dedicated people. Such positions as office manager, assistant project manager, and even positions as assistant estimators await those who can perform.

a. Nature of Work

The role of an architect involves numerous job descriptions including production drawings, design, specifications, construction document production, computer–aided design, and project management. These tasks apply to design in many different types of fields such as building, energy conservation, historic preservation, interiors, site planning, facilities management, landscape design, graphics, and urban planning. The design element of architecture requires sensitivity to the environment. Architects learn to discover new and creative ways of problem solving under diverse and changing conditions with known and unknown constraints.

b. Education and Training

The architect needs to prepare for his or her career in high school by taking a broad range of courses which should include art, English, history, social studies, mathematics, physics, foreign languages, business, and computer science. It is helpful to have freehand drawing skills as well as rudimentary drafting ability and an interest in the natural and built environments. It is important to apply early to a school of Architecture (accredited by the National Architectural Accrediting Board), as admission is often competitive. The bachelor degree involves a five–year undergraduate and graduate program, or a four–year liberal arts degree (undergraduate) followed by a two to three–year graduate degree.

c. Advancement Potential

Advancement within the field of architecture often involves becoming a registered architect. This is accomplished by passing a state board licensing test which can be taken after fulfilling certain obligations (which vary from state to state). The obligations typically include internship for at least a three–year period under a professional architect. At the upper levels of advancement, there are job opportunities such as firm management, business development, and marketing.

a. Nature of Work

Every construction firm needs systematic and up–to–date records of accounts and business transactions. Bookkeepers and accounting clerks maintain these records in journals and ledgers or in the memory of a computer. They also prepare periodic financial statements showing all money received and paid out. The duties of bookkeepers vary with the size of the firm. However, virtually all of these workers use calculating machines and many work with computers. In many small companies, a general bookkeeper handles all the bookkeeping. He or she analyzes and records all financial transactions such as purchase orders and cash receipts. General bookkeepers also prepare and mail customer’s bills and answer telephone requests for information about orders and bills. In large organizations, several bookkeepers and accounting clerks work under the direction of a head bookkeeper or accountant. Some bookkeepers prepare statements of a company’s income from sales or its daily operating expenses. Others record business transactions, including payroll deductions and bills paid and due, and compute interest, rental, and freight charges.

b. Education and Training

High school graduates who have taken business math, bookkeeping, and principles of accounting meet the minimum requirements for most bookkeeping jobs. Increasingly, employers prefer applicants who have completed accounting programs at the community college level or those who have attended business school. The ability to use bookkeeping machines, computers, and varied software programs is an asset.

c. Advancement Potential

Some bookkeepers and accounting clerks are promoted to supervisory positions after additional training and experience. Others who enroll in college accounting programs may advance to jobs as accountants.

a. Nature of Work

The Chief Financial Officer (CFO) directs and coordinates the financial objectives and obligations inside and outside of the company. His or her primary responsibility lies in maintaining a financially solvent organization.

Externally, the Chief Financial Officer is charged with the sole responsibility of establishing and maintaining sound business relationships with banking/lending institutions and other resources of capital. As a result, the CFO serves as the company’s chief financial negotiator within the financial community, securing stable and profitable working relationships for the company.

Internally, the Chief Financial Officer works with the Senior or Chief Accountant in directing and coordinating company finances. Developing budgets for both annual and interim periods as well as planning cash management investment strategies require much of his/her time. Occasionally, the CFO will give an economic appraisal of the company and in doing so, will prepare relevant financial ratios and reports.

b. Education and Training

Today’s Chief Financial Officer typically requires a four–year college degree in Accounting, with many having advanced degrees such as a Masters of Business Administration (MBA). Equally important to the CFO, however, are good analytical skills, an excellent rapport with superiors and subordinates, established communication skills, a solid business background, and the ability to lead people.

c. Advancement Potential

The Chief Financial Officer is usually considered one of the top officers in a construction company’s organizational structure. He or she generally starts as an accountant. The CFO is always considered a prime candidate for other top management positions, including the presidency.

6. Construction/Project Engineer

a. Nature of Work

The terms construction engineer and project engineer normally relate to the same person or job function. Construction engineering is the application of engineering, management, and business sciences to the processes of construction, through which designers’ plans and specifications are converted into physical structures and facilities. The construction or project engineer is a professional constructor who engages in the design of temporary structures, site planning and layout, cost estimating, planning and scheduling, management, materials procurement, equipment selection, cost control, and quality management.

These processes involve the organization, administration, and coordination of all the elements involved in construction labor, temporary and permanent materials, equipment, supplies and utilities, money, technology and methods, and time in order to complete construction projects on schedule, within the budget, and according to specified standards of quality and performance. Depending upon the size and complexity of a project, the construction engineer may be responsible for one to several jobs. This means that travel to many different work sites is part of this occupation. Many project engineers work on–site in temporary offices and spend a good deal of time out of doors, planning and checking work.

b. Education and Training

Construction engineers must have a strong fundamental knowledge of engineering and management principles, and knowledge of business procedures, economics, and human behavior. Students who wish to pursue a career as a construction or project engineer should concentrate on math and science courses, and must earn above average grades in high school. A bachelor’s degree is virtually required for this career, and students must be very careful in selecting an accredited academic engineering degree program with a major emphasis or concentration in construction. Those who do not concentrate in construction engineering at the undergraduate level may return to school for a master’s degree in engineering management or business administration.

c. Advancement Potential

Construction engineers typically begin their careers in a training capacity as engineers–in–training. They may begin as assistants to project superintendents, project managers, estimators, or field engineers. Advancement and responsibility are quickly earned for those who excel. It is not unusual for construction engineers to be in total charge of small projects within five years of employment. Construction/project engineers frequently become the chief operating officer of companies.

a. Nature of Work

A constructor is an individual who utilizes skills and knowledge, acquired through education and experience, to manage the execution of all or a portion of a construction project. The constructor can be involved in building many types of facilities including, but not limited to, commercial (i.e., office buildings and shopping centers), institutional (i.e., hospitals and schools), industrial (i.e., factories and refineries), residential (i.e., homes and apartments), and civil (i.e., highways and utilities).

A constructor is primarily employed by or works as a general (or prime) contractor or a sub (or specialty) contractor. One can also find constructors working in other types of organizations such as construction management firms, architectural/engineering offices, material suppliers, governmental agencies, financial institutions, and for users of construction which have their own in–house construction management personnel.

Because the typical construction project is comprised of many different types of personnel, equipment, materials, and activities, the constructor must possess a wide variety of skills and knowledge. These include being able to read and interpret architectural/engineering drawings and specifications; understanding and complying with numerous local and state building codes, legal requirements, and construction standards; understanding and adherence to a variety of construction contract conditions and requirements; efficiently estimating cost and scheduling all or a part of a project; and the performance of management duties required to effectively coordinate and communicate with all members of the construction process.

The work environment of a constructor is varied, ranging from work in comfortable permanent offices to working on the project site in a small temporary office. Constructors spend a great deal of their time working with the project designers (owner representatives), clients (owner), and with other constructors, foremen, and/or other employees who are responsible for the day–to–day work in the field. Writing and reviewing reports in order to discuss work schedules and progress can consume a large portion of the constructor’s time. Extensive travel is not unusual.Constructors typically work long hours, and must meet critical production deadlines. Weekend work is common.

b. Education and Training

The vast majority of today’s constructors are college educated, and those planning a career in construction should strive for a baccalaureate degree. While the construction industry will always require many persons educated solely as architects, engineers, or in pure managerial skills, the most effective education for constructors, at all levels of managerial responsibility, is a meaningful synthesis of general education, math and science, construction design, construction techniques, and business management at the undergraduate level. Typical construction program courses include mathematics and English, history and economics, physics, strength of materials, structural design, mechanical and electrical systems, materials and methods, planning, estimating, scheduling, technical report writing, contract documents, business management, and contract law.

Degrees in Construction are now available at over 100 colleges and universities. Although they may have different titles, all are generally classified as Construction, Construction Science, Construction Management, Construction Technology, Building Science, or Construction Engineering. The American Council for Construction Education (ACCE) accredits pure construction degree programs while the Accreditation Board for Engineering & Technology (ABET) accredits construction engineering and construction technology programs. In 1996 there were 43 ACCE accredited programs. There are also six construction engineering programs, and about 45 construction technology programs accredited by ABET. Entrance requirements range from average to above average high school grades and scores on standardized tests (i.e., SAT, ACT). Students may transfer to construction degree programs from two–year junior and community colleges.

Although higher education is desirable, the construction industry remains one of the few American industries where one may start with little formal education and still reach the top by becoming a chief executive or owner of a construction firm. This path to the top, from traineeto craftsman to constructor, requires hard work and a great deal of personal dedication, and it becomes more difficult as technology advances.

c. Advancement Potential

New graduates usually begin employment with construction firms as assistant estimators, assistant project managers, or at some other mid–management position. As such, they are immediately involved in the day–to–day operations of the firm or a construction project. Responsibility comes quickly and advancement is relatively rapid in this fast–paced occupation. However, it takes many years of experience and responsibility before a graduate is considered an accomplished constructor.

a. Nature of Work

A draftsman translates a designer’s ideas into a finished picture using drawing and drafting skills. The drawings produced will be used as a guide by every other link in the chain of construction, both on–site and in the office. The draftsman must be detail–oriented and skilled in free–hand and mechanical lettering and drawings, and should have good hand–eye coordination.

b. Education and Training

Drafting courses taught in high schools, vocational–technical schools, and other training institutions are a minimum requirement. Draftsmen need a good background in math, including geometry and trigonometry. Any classes which teach the basics of mechanical drawing, lettering, and blueprint reading will be useful. Draftsmen may wish to seek additional study in mathematics and computer– aided design in order to keep up with technological progress within the industry.

c. Advancement Potential

There are numerous areas of specialization within the field of drafting, many of which lead to greater opportunity for performing actual design work. Since some firms frequently employ several draftsmen, there is potential for a management position within the drafting crew. With additional training, draftsmen may become recognized engineering technicians – individuals whose primary function is to provide technical support to the designers and engineers who work in construction.

a. Nature of Work

Engineers in construction are involved in planning, design, construction, operation, and management of engineering and engineering–construction projects. They are problem solvers, and must be concerned with both the detail and general applications and problems of their work in relation to the overall construction project. Engineers in construction may specialize in several engineering fields such as Architectural, Civil (including Structural Engineering), Electrical, and Mechanical Engineering.

i. Architectural Engineer

The architectural engineer (AE) is involved with the design of the building, and/or the estimating and supervision of the project. Initial emphasis is on building construction materials, principles, practices, and methods. An Architectural Engineer can specialize in structural design or in building environmental system design of heating, ventilating and air conditioning, fire safety systems, plumbing, or lighting/illumination. In college, the Architectural Engineering (AE) program is clearly focused on the building industry.

ii. Civil Engineer

Civil engineers work with structures. They design and monitor the construction of roads, airports, tunnels, bridges, dams, harbors, irrigation systems, water treatment and distribution facilities, and sewage collection and treatment systems. Civil engineers are technical problem solvers. They incorporate the principles of science and mathematics into the cost–effective design of permanent and temporary structures. The development of detailed plans and specifications is a major aspect of their work. Civil engineering is the oldest and broadest of the engineering professions. “Civils” can concentrate their work in technical specialties such as structural engineering and transportation engineering.

iii. Electrical Engineer

Electrical and electronics engineers design, develop, test, and supervise the manufacture and sometimes installation of electrical equipment. Such equipment includes the power generating and transmission equipment of electric utility companies, and the electric motors, machinery controls, and lighting and wiring used in buildings. Electronic equipment used in automobiles, aircraft, computers, and communications equipment is also designed by electrical engineers. The work involves writing equipment performance requirements, developing maintenance schedules, solving operating problems, and estimating the time and cost of electrical engineering projects.

iv. Mechanical Engineer

Mechanical engineers are concerned with the production, transmission, and use of mechanical power and heat. They study the behavior of materials when forces are applied to them – such as the motion of solids, liquids, and gasses – and the heating and cooling of objects and machines. Mechanical engineers design and develop manufacturing equipment and technologies, and supervise installation of refrigeration and air conditioning equipment, materials handling systems, automatic control systems, noise control and acoustics, machine tools, internal combustion engines, solar energy systems, and rail transportation equipment.

v. Structural Engineer

Structural engineering is a specialized field of work falling within the civil engineering discipline. Structural engineers are planners and designers of buildings of all types: bridges; dams; power plants; supports for equipment; special structures for offshore projects; transmission towers; and many other kinds of projects. They are experts in analyzing the forces that a structure must resist (its own weight, wind, water, temperatures, earthquakes, and other forces), and incorporate appropriate materials (steel, concrete, timber, plastic) into a design that will resist these forces and carry the total load of the structure.

b. Education and Training

Construction–oriented positions in modern engineering range from those requiring a baccalaureate degree to those requiring a master’s degree. University entrance requirements are generally those which a high school college preparatory program provides. Interested individuals should write the admissions office at their selected college for specific details. Seek a school accredited for the specific type of engineering program desired. Good College Board (SAT) or ACT scores are important, as well as good grades in junior high school and senior high school. Students with an aptitude for engineering are probably earning above average grades in mathematics and science. Above all, they should enjoy these subjects, and like to study and to achieve. Engineering students should have common sense, patience, and a strong sense of curiosity.

c. Advancement Potential

There is a place for engineers of many kinds of interests and abilities within the construction industry. Many engineering graduates begin as assistants to supervisors, office managers, or company executives. All have the potential to move into top management positions. Many construction firm owners began their careers as design engineers.

a. Nature of Work

The estimator’s job is important in every construction firm. Every type of project requires an accurate and comprehensive estimate of the amounts of materials, equipment, and labor necessary for the construction of the project. Estimators work with the engineer’s and architect’s drawings or blueprints to prepare a complete list of all job costs, including labor, material, equipment, and specialty items necessary to complete the project. Knowledge of construction techniques and proper scheduling of purchases and work are essential skills. Estimator work is generally in the office, but some field coordination is often required. Estimators may be subject to considerable stress in the days and hours before an estimate or bid is submitted, so the ability to work accurately and quickly under pressure is needed.

b. Education and Training

An estimator needs a good background in mathematics including algebra and geometry, drafting, blueprint reading, and English. Neatness and accuracy are important. Most estimators combine junior or community college courses in construction and engineering technology with on–the–job training to acquire needed skills. With the increasing use of computerized estimating systems, computer literacy is becoming another much–needed skill. College, although not a definite requirement, should be considered for early advancement.

c. Advancement Potential

The estimator’s familiarity with the plans, specifications, and materials of a construction job provides excellent preparation for a position as project manager. Indeed, the owners and officers of many construction businesses received their initial industry experience as estimators.

a. Nature of Work

An expeditor or purchasing agent is the person in charge of scheduling purchases, purchasing, and scheduling the delivery of materials and services for construction jobs. An expeditor then checks orders and speeds the arrival of building materials or equipment to meet a progress schedule. Expeditors also make sure there are enough people scheduled to work each day to get the work done. An expeditor usually works in the office, scheduling material and equipment deliveries, and in the field, scheduling the work. The position requires dealing with many different types of people.

b. Education and Training

An expeditor needs a background in construction so that he or she is familiar with all types of building materials and prices. Expeditors also need to have knowledge of and be familiar with various work categories and scheduling. Good skills in math and English are very important, and the ability to deal and get along with others can be essential. A high school diploma is usually required.

c. Advancement Potential

The rapport an expeditor or purchasing agent must establish with the other key individuals of the construction processes provides a broad business understanding which is valuable in all managerial positions. For many construction firms, the expeditor is an entry–level position open to graduates of academic engineering or construction programs. Competence and efficiency as an expeditor can lead to a superintendent’s position, management of a particular project, or even a job as project manager for all of a construction firm’s work. Owners of some construction firms began their careers as expeditors.

a. Nature of Work

A foreman supervises and coordinates the work of a crew of workers in a specific craft or trade. Foremen are primarily concerned with seeing that the workers under them do their job skillfully and efficiently, and that assigned work progresses on schedule. They deal with the routing of material and equipment, and with the laying out of the more difficult areas of the job. The work requires quick, clear thinking and quick onsite decisions. Foremen should have a broad working knowledge of a craft; must be able to read and visualize objects from blueprints; and should have an eye for precise detail.

b. Working Conditions

Working conditions for foremen can vary greatly depending upon the craft line being supervised. However, the great majority of work will be onsite and out–of–doors, often resulting in prolonged standing, as well as some strenuous physical activity.

c. Education and Training

To become a foreman, a craftsman must illustrate an above average knowledge of all facets of a particular trade and do noticeably good work consistently. A foreman should have the same basic aptitude and interests as those working in the craft being supervised, plus additional reading, writing, and math skills. The ability to motivate workers and communicate with them and superiors is essential. A foreman must often lead by example.

d. Advancement Potential

Being an entry level/first line management position, a foreman who exhibits solid rapport and communicates with his or her workers and superiors, who leads by example, who has outstanding skills and trade knowledge, who gets the job done properly and on schedule, and who works to improve his/her management skills will often be in line for promotion into a supervisory position. With the proper background and initiative, a foreman may progress to a superintendent, general superintendent, vice president, or even an owner of a construction company.

a. Nature of Work

The management information systems (MIS) manager is responsible for the effective utilization of computer technology in the organization. The MIS manager leads the planning process for future acquisition and utilization of computer hardware and software that will enable the organization to meet its short and long–term objectives. The MIS manager provides leadership, direction and control of the MIS function with budget and staffing responsibility. He or she assures training is being provided to department personnel as well as user groups. Another important area is the development and enforcement of security for all hardware, software, and information. Other responsibilities include the selection, maintenance, and operation of computer equipment and software.

Smaller companies probably will not have a manager of information systems. Leadership in the utilization of computer technology can come from any level or department in a construction company. Very often individuals who find working with computers challenging take a leadership role in defining how they can be used in the company.

Frequently, operations personnel are selected to spearhead the selection of computer equipment or software because they understand the needs and methods of the organizations.

b. Education and Training

The manager of computer information systems will most generally have at least a college degree. It is very possible, however, for an individual to work his or her way up through the organization if they have a knack for using computers and acquire the knowledge in other ways. Computer training is essential for adequately using computer equipment at any level in the organization.

c. Advancement Potential

Managers of computer systems may advance to the Vice President level of the organization. As an organization’s use of computers matures, there is a realization that information systems are an integral part of the organization and the V.P. of Information Systems is included in long range planning.

d. Other Computer–Related Positions

Although computers are used in almost any job in a construction company, there are numerous other positions that relate specifically to working with computer technology. Some of those positions are: computer operator, computer programmer, systems analyst, CAD operator, and hardware support technician. It is always most desirable to hire people for these positions with a background in the construction industry.

a. Nature of Work

The marketing manager is responsible for market research, advertising, public relations, sales, and client service. Coordination of strategic business planning, including the development and implementation of a company marketing plan, is usually the marketing manager’s responsibility. An important area of activity is the day–to–day identification of new business opportunities, whether private clients or bid work. The manager is not a sales person in the usual sense. Trust, confidence, and relationships are primary to the sale. Building the public’s awareness and recognition of the company is also the marketing manager’s job.

Communications and people skills are essential for the job, along with an optimistic and strong self–starting attitude to keep tracking down construction leads and knocking on doors. This position invites creativity and strong problem–solving skills, and requires an individual capable of juggling many activities (leads) at the same time. It is a necessity that the marketing manager be able to get all employees involved in the marketing process.

b. Education and Training

There are two schools of thought on the type of background a marketing manager needs in order to be successful. Many construction executives believe it’s best to hire a non–technical college graduate with prior sales experience, regardless of the type of sales involved. Others advocate the training of an energetic, personable project manager or anyone with a construction background and a sales personality. Both methods have been successful. A college degree and excellent writing and public speaking skills are desirable.

As owners and developers (buyers of construction services) become more knowledgeable and increasingly hire their own consultants with construction experience, knowledge of construction systems may, however, become a prerequisite for the construction firm’s marketing manager position.

c. Advancement Potential

Marketing managers often have the title of Vice President, and are considered part of the company’s upper management team. If successful, their income is usually among the top two or three in the company. They sometimes become chief executive officer of their construction firm or owner of a construction company.

a. Nature of Work

The job of a construction office manager is extremely varied, depending upon the size of firm, the type of construction work the company performs, and whether or not the position is in a field office or in the main headquarters office. Regardless of the working environment, the role of the office manager is very important.

An office manager is the person responsible for seeing that the office procedures and duties are completed in a correct and timely manner. An office manager must solve problems as they arise, and make certain that the financial information which has been compiled is correct. It is important to plan office functions in the correct sequence, so that one employee will not be delayed waiting for data which is being compiled by another employee. Almost all office manager work is done in the main office, or on a large job, in the field office.

b. Education and Training

The most important qualification of a construction company office manager is knowing how to deal with people. In addition, office managers need a bookkeeping background with emphasis on accounting subjects. High school with some college is very desirable, as good reading and writing skills may be essential. Basic knowledge of computer systems may also be helpful.

c. Advancement Potential

Office managers are usually considered as part of management.

a. Nature of Work

The position of project manager is sometimes the same as that of a general superintendent or project superintendent. The nature of a project manager’s work is, therefore, very dependent upon the firm’s organizational structure, the firm’s size, and the number or size of projects the manager works with. Generally speaking, a project manager is employed by larger firms. He or she is an individual capable of overall management responsibility for delivering a construction project from its conception until it functions as it was intended. The project manager must be capable of establishing performance and delivery criteria for approval by the owner. If one’s firm is involved in project design work, the project manager may be responsible for directing the production of basic design plans and construction documents. Estimating, start up, scheduling, actual construction, expediting, inspection, quality control, and total delivery of the project according to the established criteria are aspects of the project manager’s job.

b. Education and Training

Most project managers have many years of experience as a construction superintendent. Generally, contractors have selected their project managers from among the superintendents or occasionally foremen who demonstrate leadership and working knowledge of construction operations. A college education is very desirable, although it is not necessarily essential for some firms. At many firms, it has become a requirement, and a number of schools offer construction management degrees which combine construction procedures with administrative principles. A project manager must have a good understanding of construction methods, materials, scheduling, and blueprint reading, as well as knowledge in communication skills.

c. Advancement Potential

Project managers are usually considered top management, and often become principal officers of their construction firms. On occasion, project managers start their own company.

a. Nature of Work

The position of safety director is an important one. In some construction firms, the safety director may be an officer or senior manager of the company. The safety director’s primary responsibility is to keep the loss of human and property resources to a minimum. The safety director is an individual capable of managing jobsite safety by providing safety training for employees, inspecting jobsites, correcting safety hazards found during regular inspections, managing worker’s compensation insurance processes, and ensuring that the company is in compliance with required Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) safety and health standards.

b. Education and Training

A college education is not essential although pertinent safety training courses are desirable. A good safety director understands OSHA regulations and how they work in construction. He or she also has basic knowledge of construction operations, materials, and methods. Most safety directors have previous construction experience and a keen interest in construction safety.

c. Advancement Potential

Safety directors are often competent money makers and capable of working with individuals at all levels of the corporate ladder. The high cost of health care and expenses related to jobsite injuries, as well as the high cost of replacing and/or repairing a company’s resources including its property, equipment, and tools is prompting many construction companies to hire safety directors. Safety directors often advance to higher level management positions either in their company or in others.

a. Nature of Work

The scheduler or scheduling engineer assumes the responsibility for the overall scheduling of a construction project. He or she may be involved in one project or numerous projects. The scheduler’s responsibilities include a wide range of duties involving initial job planning, scheduling of time, scheduling of materials, coordination of subcontractors, monitoring of job progress, analysis of changes, and problem solving. Specifically, the scheduler will produce the contractor’s initial schedule and then update the schedule throughout construction. He or she will also use the schedule to analyze the impact of change orders, delays, and any other schedule disruptions.

The scheduler works very closely with the project manager, project superintendent, and the subcontractors during the preparations and updating of the construction schedule. Because of this, the scheduler must possess good communication skills. He or she will continually be producing critical scheduling information for the project team’s use, very much like an accountant produces financial information for a company’s managers. Therefore, the scheduler maintains an important support role to the project superintendent, project manager, and all other parties associated with the project.

b. Education and Training

In the past, the role of a scheduler or scheduling engineer was handled by the project superintendent, the project manager, or both. Their scheduling education basically consisted of many years of experience working on construction projects.

Today, many general contracting firms have schedulers on their staff or they retain the needed talent by using outside consultants. These schedulers normally have a college degree in an engineering discipline, architecture, or construction management. They must have a good understanding of construction practices, procedures, and the methods of construction. The scheduler must also be proficient in reading construction drawings. Since most construction scheduling is accomplished using the Critical Path Method (CPM), schedulers must have knowledge and experience in this technique. CPM Scheduling, now taught in most colleges, has become a basic requirement for all schedulers.

Also, since computers are used to prepare CPM schedules, knowledge and experience in the use of computers and scheduling applications are very advantageous.

c. Advancement Potential

Schedulers are considered part of the management staff; many continue on to become project superintendents, estimators, project managers, or project executives.

There are many types of construction superintendents and their job titles, job descriptions, and responsibilities vary a great deal from one company to another. This can be confusing, and there are no hard and fast rules or definitions which apply to all construction firms, all construction projects, or all supervisory positions. A general sequence of titles is indicated below, but it must be noted that many are used interchangeably, and duties will vary by firm and project(s) size. The thing to remember, therefore, is that the position of “Superintendent” involves increasing degrees of responsibility and authority – regardless of the title.

a. Nature of Work

Generally speaking, a job superintendent or project superintendent is the contractor’s representative at a construction site. The superintendent directs and coordinates the activities of the various trade groups such as carpenters, equipment operators, iron workers, etc. – on site. Responsibilities include making sure that the work progresses according to schedule, that material and equipment are delivered to the site on time, and that the activities of the various workers do not interfere with one another. The superintendent supervises all these activities by talking with and directing the foremen for the different trades or craft workers. Some of these foremen and their workers may be employed by the superintendent’s own construction company, while others may be employed by other companies working on the job.

As stated, the responsibilities of a job and/or project superintendent are often the same. Yet, in some instances either one (especially the project superintendent) may be over the superintendent(s) in charge of a specific jobsite’s activities, e.g. grading. In the same sense, a general superintendent (often found on larger jobs and/or with large firms) may have duties similar to the project superintendent mentioned above, but with an even broader range of responsibilities. A general superintendent might direct the work on a number of construction sites with those superintendents reporting to him. A “Project Manager” is another construction occupation title for a position which again may overlap and, on occasion, be used interchangeably with general, project, or job superintendent. A review of the definition for Project Manager might be helpful.

b. Education and Training

Most superintendents have many years of experience in one of more of the construction trades. Generally, contractors have selected their superintend-ents from among the foremen who demonstrate leadership and a working knowledge of their craft. While a college education is not necessarily required, it is helpful. A superintendent must have a good understanding of construction methods, scheduling, and blueprint reading, as well as a basic knowledge of communication skills. Demonstrated leadership ability is essential.

c. Advancement Potential

Depending upon the size of the firm (and the job titles used by that firm), job or project superintendents may become general superintendents. Superintendents often become principal officers of their construction firm, and on occasion start their own company.

Field construction boilermakers are involved in more that just the construction and repair of boilers. Boilermakers are a vital part of construction project teams that erect and repair pressure vessels, air pollution equipment, blast furnaces, water treatment plants, storage and process tanks, stacks and liners. Boilermakers’ work demands a high degree of technical skill and knowledge, a dedication to excellence, and an ability to travel from job site to job site to maintain employment. A boilermaker must understand and work from blueprints, and be able to use measuring, leveling, and aligning tools to check their work.

a. Working Conditions

Field construction work is by nature an outside job which means exposure to all types of weather conditions, including extreme heat and cold. Boilers, dams, power generation plants, storage tanks, and pressure vessels are usually of mammoth size; therefore, a major portion of boilermaker work is performed at great heights, often from 200 to 1000 feet above the ground. Field construction and repair work is contract work; so, when the contract is completed, the job is ended. You may have to travel the territory of the work and live away from home for long periods of time. The size of the materials, tools, and equipment handled by boilermakers requires excellent physical strength and stamina.

b. Aptitude and Interest

Boilermaker construction involves a variety of duties requiring close tolerances and standards. Boilermaker requires careful, accurate work by the craftsman. They will work with burning and gouging equipment; removing and replacing pressured and non-pressure components; interpreting blueprints; laying out components; using various welding equipment and process; and aligning and fitting components. Good eyesight is important to quickly determine lines and levels. Also, manual dexterity is especially important.

c. Training

To become a skilled boilermaker, training is essential. It can be acquired informally through “learning–by–working;” through company on–the–job training programs; by attending trade or vocational/technical schools; through unilaterally (management or labor) sponsored trainee programs; through registered, labor–management apprenticeship programs; or a combination of the above. It is generally accepted that the more formalized training programs give more comprehensive skill training. Recommended high school courses include algebra, geometry, general science, mechanical drawing, and English.

Bricklayers construct walls, partitions, fireplaces, chimneys, and other structures from brick, block, and other masonry materials such as structural tile, concrete cinder, glass, gypsum and terra cotta. They spread a layer or “bed” of soft mortar that serves as base and binder using a trowel. The brick or block is then positioned and the excess mortar removed. Bricklayers must understand and work from blueprints, and be able to use measuring, leveling, and aligning tools to check their work.

a. Working Conditions

Much of masonry work is out–of–doors and depends on suitable weather. However, modern construction methods along with heaters and temporary enclosures stretch the season and make bricklayers less dependent on good weather. Bricklayers are on their feet all day, and do considerable lifting of heavy materials with much bending – sometimes from scaffolding high above the ground.

b. Aptitude and Interest

Masonry construction involves a variety of duties requiring close tolerances and standards. Bricklaying requires careful, accurate work by the craftsman. Masons should enjoy working outside under many different weather conditions. Good eyesight is important to quickly determine lines and levels. Also, manual dexterity is especially important.

c. Training

To become a skilled bricklayer, training is essential. It can be acquired informally through “learning–by–working;” through company on–the–job training programs; by attending trade or vocational/technical schools; through unilaterally (management or labor) sponsored trainee programs; through registered, labor–management apprenticeship programs; or a combination of the above. It is generally accepted that the more formalized training programs give more comprehensive skill training. Recommended high school courses include algebra, geometry, general science, mechanical drawing, and English.

Carpenters possess skills and perform work which is basic to most building construction. They erect wood framework in buildings; build forms for concrete; and erect partitions, studs, joints, drywalls, and rafters. Many carpenters work indoors to install all types of floor coverings, ceilings, paneling, trim, and interior systems. They must be very skillful as “finish” work is visible and often involves expensive materials. Some carpenters construct docks and work with large timbers and drive piles to support the foundations of buildings and bridges. Another branch of the trade, called millwrights, installs heavy machinery in industrial plants and turbine generators in power plants. All carpenters use a wide variety of hand and power tools, and they must be able to maintain their tools in good, safe working order.

a. Working Conditions

Carpenters usually work with or around other construction tradesmen. They work indoors and outdoors and often in tight places. All carpenters have to do considerable climbing, lifting, and carrying to perform their work. They must also be able to do a great deal of reaching, balancing, kneeling, crawling and turning.

b. Aptitude and Interest

To be a good carpenter, a person should enjoy doing precision work, have pride of craftsmanship, the ability to work without close supervision, and be able to adapt to a wide variety of conditions. Manual dexterity and the ability to solve math problems quickly and accurately are necessary for those who wish to become top craftsmen.

c. Training

To become a skilled carpenter, training is essential. It can be acquired informally through “learning–by–working;” through company on–the–job training programs, by attending trade or vocational/technical schools; through unilaterally (management or labor) sponsored trainee programs; through registered labor–management apprenticeship programs, or a combination of the above. It is generally accepted that the more formalized training programs give more comprehensive skills training. Recommended high school courses include algebra, general science, mechanical drawing, English, blueprint reading, and general shop.

Cement masons level, smooth, and shape surfaces of freshly poured concrete on projects ranging from patios and basements to dams, highways, and foundations and walls of building.

Cement masons must have a thorough knowledge of concrete characteristics and related materials. Also, they must know the effects of heat, cold, and wind on the curing of concrete. They must be able to tell by sight and touch what is happening to concrete in order to prevent defects.

a. Working Conditions

Since much of the concrete finishing is done outdoors, working conditions are governed by the weather. Concrete is not usually placed in rain or when temperatures are below freezing. However, the work, either indoor or outdoors, may be in areas that are muddy, dusty, and dirty. The work requires continuous physical effort.

b. Aptitude and Interest

Finishers should enjoy doing demanding work. They should have pride of craftsmanship and be able to work without close supervision.

c. Training

To become a skilled cement mason, training is essential. It can be acquired informally through “learning–by–working;” through company on–the–job training programs; by attending trade or vocational/technical schools; through unilaterally (management or labor) sponsored trainee programs; through registered labor–management apprenticeship programs, or a combination of the above. It is generally accepted that the more formalized training programs give more comprehensive skill training. Recommended high school courses include English, math, mechanical drawing, and general science.

Electricians lay out, install, and test electrical service and electrical wire systems used to provide heat, light, power, air conditioning, and refrigeration in homes, office building, factories, hospitals, and schools. They also install conduit and other materials, and connect electrical machinery, equipment, and controls and transmission systems.

a. Working Conditions

Electricians work both in and outside. They work in all kinds of weather while installing grounding and temporary lights and power. The work is active and strenuous with much of it done in awkward positions and frequently in cramped quarters. They must do considerable standing, reaching, bending, stooping, climbing, carrying, and lifting in order to install electrical conduit and equipment.

b. Aptitude and Interest

Applicants interested in becoming electricians must enjoy working with math problems and be able to work with fine measurements. They must be able to work very carefully, without close supervision, have steady nerves, and possess a great deal of patience. Prospective electricians should have above average intelligence, the ability to visualize detailed sketches, finger dexterity, understanding of electrical theory, and be able to plan sequences of operations. Good color vision is also important.

c. Training

To become a skilled electrician, training is essential. It can be acquired informally through “learning–by–working;” through company on–the–job training programs; by attending trade or vocational/ technical schools; through unilaterally (management or labor) sponsored trainee programs; through registered labor–management apprenticeship programs, or a combination of the above. It is generally accepted that the more formalized training programs give more comprehensive skill training. Recommended high school courses include English, algebra, geometry, trigonometry, physics, mechanical drawing, blueprint reading, and general shop.

Elevator constructors perform the construction, operation, inspection, testing, maintenance, alteration, and repair of elevators, platform lifts, stairway chair lifts, escalators, moving walks, dumbwaiters, material lifts, and automatic transfer devices. They also perform the construction, operation, inspection, maintenance, alteration and repair of automatic guided transit vehicles such as automated people movers. Individuals perform this work while working at heights, around exposed electrical contacts and moving sheaves and cables.

a. Working Conditions

Elevator constructors lift and carry heavy equipment and parts, and they may work in cramped spaces or awkward positions. Most of their work is performed indoors in existing buildings or buildings under construction.

Most elevator constructors work a 40-hour week. However, overtime is required when essential equipment must be repaired, and some workers are on 24-hour call. Because most of their work is performed indoors in buildings, elevator installers and repairers lose less work time due to inclement weather than do other construction trades workers.

b. Aptitude and Interest

Applicants interested in becoming elevator constructors must enjoy working with math problems and be able to work with fine measurements. They must be able to work very carefully, without close supervision, have steady nerves, and possess a great deal of patience. Prospective elevator constructors should have above average intelligence, the ability to visualize detailed sketches, finger dexterity, and be able to plan sequences of operations.

c. Training

To become a skilled elevator constructor, most learn their trade in an apprenticeship program administered by local joint educational committees representing the employers and the union—the International Union of Elevator Constructors. In nonunion shops, workers may complete training programs sponsored by independent contractors.

Applicants for apprenticeship positions must have a high school diploma or the equivalent. High school courses in electricity, mathematics, and physics provide a useful background. As elevators become increasingly sophisticated, workers may need to get more advanced education.

Carpet, tile, and other types of floor coverings not only serve an important basic function in buildings, but their decorative qualities also contribute to the appeal of the buildings. Carpet, floor, and tile installers and finishers lay floor coverings in homes, offices, hospitals, stores, restaurants, and many other types of buildings. Tile also may be installed on walls and ceilings.

a. Working Conditions

Carpet, floor, and tile installers and finishers usually work indoors and have regular daytime hours. However, when floor covering installers need to work in occupied stores or offices, they may work evenings and weekends to avoid disturbing customers or employees. By the time workers install carpets, flooring, or tile in a new structure, most construction has been completed and the work area is relatively clean and uncluttered. Installing these materials is labor intensive; workers spend much of their time bending, kneeling, and reaching—activities that require endurance. The work can be very hard on workers’ knees and back. Carpet installers frequently lift heavy rolls of carpet and may move heavy furniture, which requires strength and can be physically exhausting.

b. Aptitude and Interest

Carpet, floor, and tile installers and finishers should be patient and careful workers. Good manual dexterity, ability to align things by eye, physical fitness, and a good sense of balance and color are also important assets. The ability to solve basic math problems quickly and accurately also is required.

c. Training

To become a skilled floor layer, training is essential. It can be acquired informally through “learning–by–working;” through company on–the–job training programs; by attending trade or vocational/technical schools; through unilaterally (management or labor) sponsored trainee programs; through registered labor–management apprenticeship programs, or a combination of the above. It is generally accepted that the more formalized training programs give more comprehensive skill training. Recommended high school courses include general mathematics, blueprint reading, and general shop.

In the construction industry, glaziers are responsible for the sizing, cutting, fitting, and setting of all glass products into openings of all kinds. Basically, glaziers perform two types of glass settings. The first and most common is the installation of glass in windows and doors. The second type of glass work is the installation of structural glass. This type of glass is used as decoration for ceilings, walls, building fronts, and partitions.

a. Working Conditions

Glaziers sometimes work alone on small jobs, but usually they work in crews on larger jobs where it takes several glaziers to carry, position, and set the huge pieces of glass. There is much lifting, carrying, and climbing.

b. Aptitude and Interest

Glaziers should be patient and careful workers. Good manual dexterity and the ability to align things by eye are also important assets.

c. Training

To become a skilled glazier, training is essential. It can be acquired informally through “learning–by–working;” through company on–the–job training programs; by attending trade or vocational/technical schools; through unilaterally (management or labor) sponsored trainee programs; through registered labor–management apprenticeship programs, or a combination of the above. It is generally accepted that the more formalized training programs give more comprehensive skill training. Recommen

Properly insulated buildings reduce energy consumption by keeping heat in during the winter and out in the summer. Vats, tanks, vessels, boilers, steam and hot-water pipes, and refrigerated storage rooms also are insulated to prevent the wasteful loss of heat or cold and to prevent burns. Insulation also helps to reduce the noise that passes through walls and ceilings. Insulation workers install the materials used to insulate buildings and equipment. Insulation workers cement, staple, wire, tape, or spray insulation.

a. Working Conditions

Insulators generally work indoors in residential and industrial settings. They spend most of the workday on their feet, either standing, bending, or kneeling. They also work from ladders or in confined spaces. Their work usually requires more coordination than strength. In industrial settings, these workers often insulate pipes and vessels at temperatures that may cause burns. Workers must follow strict safety guidelines to protect themselves. They keep work areas well ventilated; wear protective suits, masks, and respirators; and may take decontamination showers when necessary.

b. Aptitude and Interest

Applicants should be able to work with numbers and work well with their hands. They must be able to follow instructions and work closely from shop drawings and blueprints.

c. Training

To become a skilled insulator, training is essential. It can be acquired informally through “learning–by–working;” through company on–the–job training programs; by attending trade or vocational/technician schools; through unilaterally (management or labor) sponsored trainee programs; through registered labor–management apprenticeship programs, or a combination of the above. Trainees in formal apprenticeship programs receive in-depth instruction in all phases of insulation. Apprenticeships are generally offered by contractors that install and maintain industrial insulation. Recommended high school courses include blueprint reading, mathematics, science, sheet metal layout, woodworking, and general construction.

Structural iron workers erect the steel framework for large industrial, commercial, or residential buildings, bridges, and metal tanks. They erect, bolt, rivet, or weld the fabricated structural metal members that support the structure during and after construction. Some iron workers, called rodmen, set steel bars (rebar) or steel mesh in forms to strengthen concrete buildings, bridges, and highways. Other iron workers, called ornamental iron workers, install and assemble grills, canopies, stairways, iron ladders, decorative iron railings, posts, and gates.

a. Working Conditions

Iron workers work in crews, usually outdoors. Work is highly seasonal and dependent upon suitable weather conditions. They frequently work in high places and cramped quarters. There is considerable climbing, walking, sitting, and balancing on ladders and girders.

b. Aptitude and Interest

Iron workers must receive satisfaction from working with their hands. They must be able to work to rigid standards and fine measurements. They must have an acute awareness of dangers to both themselves and their co–workers. Also, ironworkers can not be afraid of work in high places.

c. Training

To become a skilled iron worker, training is essential. It can be acquired informally through “learning–by–working;” through company on–the–job training programs; by attending trade or vocational/technician schools; through unilaterally (management or labor) sponsored trainee programs; through registered labor–management apprenticeship programs, or a combination of the above. It is generally accepted that the more formalized training programs give more comprehensive skill training. Recommended high school courses include English, general math, algebra, geometry, physics, mechanical drawing, and welding.

Laborers range from unskilled to semi–skilled workers whose duties include but are not limited to handling the materials of bricklayers, cement masons, and carpenters. Laborers are generally needed on virtually all types of construction projects – highways, bridges, tunnels, large buildings, sanitation, residential, etc. – and they are usually employed on–site from the day the project begins until the day it is completed. A laborer must know how to work with his/her hands and with power tools run by gasoline, electricity, and compressed air. They may work with pavement breakers, reamers, pumps, compressors, lasers, and vibrators. Laborers clear timber and brush, place and vibrate concrete, landscape, install pipe, and do a variety of other jobs.

a. Working Conditions

Laborer work is performed both indoors and outdoors and may be done at a surface environment, at extreme heights, underground, or above or under water. All laborers should expect to do a considerable amount of lifting, carrying, climbing, kneeling, balancing, and even crawling. Thus, a certain amount of strength, dexterity, and alertness is required. Because laborers work in so many varied conditions, they must be very knowledgeable of the hazards and safety requirements of the job.

b. Aptitude and Interest

As a supporter of other skilled craftsmen, laborers’ work requires that their skills be diversified. It is not enough to have a strong back and will to work. Laborers should master basic reading and math skills necessary to operate today’s increasingly complex and highly technical tools, equipment, and instruments.

c. Training

To become a skilled productive laborer, training is important. It can be acquired informally through “learning–by–working;” through vocational/technical schools; through unilaterally (management or labor) sponsored trainee programs; through registered, labor–management apprenticeship programs, or a combination of the above. It is generally accepted that the more formalized training programs give more comprehensive skill training. Recommended high school courses include English and basic math.

Operating engineers or equipment operators operate and maintain a variety of powerful equipment ranging from bulldozers, backhoes, and earthmovers to very large power shovels and cranes. They also lubricate, maintain, and perform minor repair and adjustment to the machinery.

a. Working Conditions

Because almost all the work is out–of–doors, working conditions are governed by the weather. The work is physically demanding and operators are subject to jarring, jolting, and continuous noise. Working with the equipment offers danger of injury and requires constant attention.

b. Aptitude and Interest

Operators much have good eyesight and better than average coordination in order to operate both hand and foot levers simultaneously. They must have good judgment in order to perform complicated tasks, and must be able to work closely with other crafts without constant supervision. Skilled operators are constantly alert and observant of their surroundings.

c. Training

To become a skilled equipment operator, training is essential. It can be acquired informally through “learning–by–working;” through company on–the–job training programs; by attending trade or vocational/technical schools; through unilaterally (management or labor) sponsored trainee programs; through registered labor–management apprenticeship programs; or a combination of the above. It is generally accepted that the more formalized training programs give more comprehensive skill training. Recommended high school courses include English, algebra, geometry, general sciences, and mechanical drawing.

These are two separate skills, but many craftsmen learn to do both. The methods of preparation and application are different, but both jobs are concerned with covering walls and surfaces. Painting includes the preparation of surfaces and the application of paint, varnish, enamel, lacquer, and similar materials to wood, metal, or masonry buildings. Painters may apply the paint with a brush, a spray gun, or a roller. They also mix pigments, oils, and other ingredients to obtain the required color and consistency. Paperhangers must also prepare surfaces. They have great skills to measure the surface, cut the wallpaper to size, paste, position and match designs, and work the air bubbles out to leave a smooth surface. A wide variety of specialized tools help throughout the process. They also learn to work with many fabrics, vinyl, or other materials.

a. Working Conditions

Painters work on floors, walls, ceilings, and equipment in interiors, and outside on everything from foundations to water towers and flag–poles. Odors from paints, thinners, or shellac are usually present. Painters may work alone or in crews. Painters and paperhangers stand, stoop, turn, crouch, crawl, kneel and frequently climb scaffolds and ladders. Safety in this occupation depends on caution and safe practices while working.

b. Aptitude and Interest

Applicants should be able to work with numbers and work well with their hands. To qualify for some jobs, the ability to distinguish between colors might be necessary.

c. Training

To become a skilled painter or paperhanger, training is essential. It can be acquired informally through “learning–by–working;” through company on–the–job training programs; by attending trade or vocational/technical schools; through unilaterally (management or labor) sponsored trainee programs; through registered labor–management apprenticeship programs, or a combination of the above. It is generally accepted that the more formalized training programs give more comprehensive skill training. Recommended high school courses include art, chemistry, general shop, interior decorating, math, and woodwork finishing.

Pipefitters / steamfitters / sprinklerfitters work from blueprints to determine the types and placement location of piping, valves, and fixtures to be installed. Pipefitters / steamfitters / sprinklerfitters assemble, install, and maintain pipes to carry liquids, steam, compressed air, gases, and fluids needed for processing, manufacturing, heating, and cooling. They must be able to change and repair pipe systems and do all types of pipe welding. They measure, cut, bend, and thread pipes, joining sections together as necessary using elbows, “T” joints, or other couplings. Pipefitters / steamfitters / sprinklerfitters install and repair high pressure pipe systems, especially in industrial and commercial establishments. After a pipe system is installed, pipefitters / steamfitters / sprinklerfitters check for leaks by forcing liquid steam or air through it under pressure. Tools used include wrenches, reamers, drills, hammers, chisels, saws, gas torches, gas or electric welding equipment, pipe cutters, benders, and threaders.

a. Working Conditions

Pipe work is active and sometimes strenuous. The work is subject to hot and cold temperatures and fumes. Frequently it is necessary to stand for prolonged periods on ladders or on scaffolds. Occasionally pipefitters / steamfitters / sprinklerfitters must operate in cramped or uncomfortable positions. The work may be indoors or outdoors in unfinished sections of new buildings.

b. Aptitude and Interest

Applicants should be able to understand detailed written and verbal instructions. They must enjoy working with their hands and working outdoors. Also, they must be able to solve arithmetic problems quickly and accurately.

c. Training

To become a skilled pipefitter / steamfitter / sprinklerfitter, training is essential. It can be acquired informally through “learning–by–working;” through company on–the–job training programs; by attending trade or vocational/ technical schools; through unilaterally (management or labor) sponsored trainee programs; through registered labor–management apprenticeship programs, or a combination of the above. It is generally accepted that the more formalized training programs give more comprehensive skill training. Recommended high school courses include English, general math, algebra, geometry, trigonometry, general science, physics, and mechanical drawing.

Plasterers finish interior walls and ceilings with plaster materials, and apply durable cement plasters, polymer–based acrylic finishes, and stucco to exterior surfaces. When working with interior surfaces such as cinder block and concrete, they first apply a brown coat that provides a base, and then a second or finish (white) coat, which is a lime–based plaster. A primary base or scratch coat is necessary when plastering over a wire mesh (metal lath). For the finish coat, plasterers prepare a mixture of lime, portland cement, and water. This is quickly and carefully applied to the brown coat with a special tool known as hawk, a trowel, or a brush and water. It dries rapidly into a smooth durable finish. Modern drywall and wallboard surfaces may require only a single finish coat of plaster material. For exterior work, plasterers apply a mixture of portland cement and sand (stucco) over concrete, masonry, or lath. Small stones are sometimes added to the mixture to create a decorative finish.

a. Working Conditions

Because the plaster material can freeze, heat is usually necessary when applying plaster, and is needed to cure or dry it after it is applied. As a result, plasterers seldom work in cold conditions, and most plastering jobs are indoors. Some plasterers, however, do work outside when applying stucco to exterior surfaces. This type of work is more popular in the warmer parts of the country. Plastering is physically demanding, requiring considerable standing, bending, lifting, and reaching overhead. Good balance is required because plasterers frequently work from ladders and sometimes from scaffolds high above ground. The work can be dusty and dirty, and the plaster material soils shoes and clothing.

b. Aptitude and Interest

Plasterers must be very good with their hands and have very good eyesight, as the job requires the creation of both smooth and sometimes decorative surfaces. They should have no fear of heights, and the ability to read blueprints is often helpful.

c. Training

To become a skilled plasterer, training is essential. This training can be acquired informally through learning–by–working with an experienced plasterer, through registered labor–management apprenticeship programs, through company on–the–job training programs, and possibly by attending a trade or vocational–technical school. Although it is generally accepted that the more formalized training programs give more comprehensive skill training, most young men and women entering this occupation begin their career as helpers to experienced plasterers. Recommended high school courses include general mathematics, mechanical drawing, and shop.

Plumbers are skilled craftsmen who install, repair, and alter pipe systems that carry gases, water and other liquids required for sanitation, storm water, industrial production, and other uses. They install plumbing fixtures, appliances, bathtubs, basins, sinks, showers, and grease line systems. They work from blueprints and working drawings to determine materials required for installation. They cut and thread pipe using pipe cutters, cutting torches, and pipe threading machines.

a. Working Conditions

Plumbers may have to work indoors or outdoors on a ladder or scaffold, underground in a trench, a crawl space under a building, or in the unfinished basement of a new building. Some of the work is dirty and messy in dusty or muddy conditions. The work is active and strenuous, with standing, bending, crawling, lifting, pulling, and pushing, and is often done in strict accordance with the state plumbing and mechanical code regulations.

b. Aptitude and Interest

A plumber works to solve a variety of problems. As in most service occupations, plumbers need to get along well with all kinds of people, and they can get called out during evenings, weekends, or holidays to perform their job.

c. Training

To become a skilled plumber, training is essential. It can be acquired informally through “learning–by–working;” through company on–the–job training programs; by attending trade or vocational/ technical schools; through unilaterally (management or labor) sponsored trainee programs; through registered labor–management apprenticeship programs, or a combination of the above. It is generally accepted that the more formalized training programs give more comprehensive skill training. Recommended high school courses include English, math, drafting, blueprint reading, physics, and chemistry.

Roofers apply built–up composition roofing and many other materials such as tile, slate, composition shingles, metals, various types of plastic materials, and other surfaces. Roofers also remove old materials in preparation for new roofing material. Some of the equipment they use are tar kettles, power–operated hoists and lifts, compressors, shingle removing equipment, and spray rigs.

a. Working Conditions